'I will be glad when it comes spring if I live to see it'

Highland Mills. Sheila Conroy reports on how the Spanish Flu affected the lives of people in the Town of Woodbury more than a century ago.

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from an article written by Sheila Conroy for the Woodbury Historical Society two years ago. It is reprinted with permission.

Woodbury Historical Society chair Dorothy Morris solemnly noted that 2017 marked the 100th commemoration of the U.S. entrance into World War I and listed Woodbury men who honorably served.

The year 2018 also marks another memorable event that likely touched many of our relatives, here and world-wide. This was the 1918-1920 flu pandemic which affected almost one-third of the world’s population. Casualties of World War I numbered about 11,000,000 military personnel and 7,000,000 civilians. The flu killed between 30,000,000 to 50,000,000 in a little over two years. (The numbers are not firm partially because hospitals and medical personnel were so overwhelmed they could not keep an accurate accounting as deaths rapidly mounted).

A personal story

I have been researching this event, partially because it has become personal to me. Growing up, I had heard the story of how the flu had taken my great grandfather’s life. My grandfather, who was age 19, was stricken next and woke up days later to learn that his father had died and was already buried. (Burials were rushed in hopes of slowing the spread of the disease and deal with the rapidly increasing numbers of fatalities). He and his older siblings would now be responsible to look after their widowed mother (age 49) and 11-year-old sister.

Recently, I discovered that three more family members succumbed to this illness; there will likely be more. In searching your own family records, if you come across relatives who died in this time period, it is very likely they were afflicted by the flu. Families living in Woodbury would not be spared either.

The end of war, the start of something else

As the fall of 1918 approached and World War I was drawing to a close, people felt great relief that the war was almost over. They looked forward to troops coming home and returning to “normal lives” after the brutality of trench warfare and poison gas.

That spring, a few people developed what was believed to be common cold symptoms which suddenly took a bad turn, resulting in death. Nobody suspected that this would turn into a world-wide killer.

In only two years, 25 percent of all Americans would become infected with around 675,000 dying. Some reports suggest that as many as 50 percent of American war casualties could have been, directly or indirectly, the result of the flu, not combat wounds. Journalist Gina Kolata, who has written a book on this subject, found that the flu infected 40 percent of the U.S. Navy and 36 percent of the Army.

How ironic that 1918 would be known as both a year of the war ending with promises of peace and a year of suffering and death from a mysterious illness.

No medicines to treat or prevent

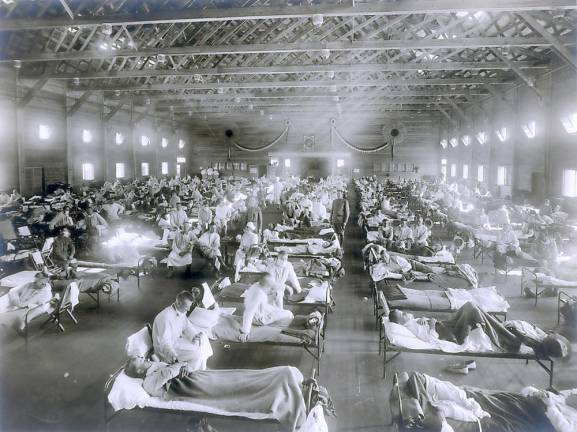

Because professionals had never seen anything like this, it was unclear what should be done to prevent or slow the spread of the flu. There were no medicines to treat or prevent it. It was the result of a virus, which was an unknown cause at the time. Hospitals were so overwhelmed and overcrowded that schools and even private homes were converted into makeshift facilities, staffed by medical students when there were not enough doctors available. Some communities began setting up tents to handle the overflow.

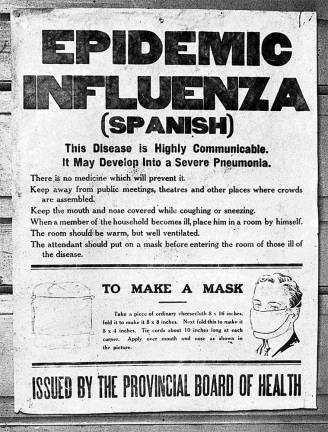

People were urged to stay indoors or wear face masks if going outside. Health officials believed that one preventive measure was to reduce public gatherings.

Schools, churches and offices in many communities throughout the U.S. closed.

Libraries stopped lending books for fear of spreading germs.

Store sales were prohibited to avoid attracting crowds.

Funerals were limited to no more than 15 people.

Ignoring rules could result in severe fines. Health care personnel, grave-diggers and morticians were pushed to the limit and were unable to treat or bury people in a timely manner. Coffins became so scarce that they had to be protected by armed guards in order to prevent thefts. Medical supplies could not keep up with demand.

The Seaman family diaries

We have a first-hand glimpse of the toll the flu had on Woodbury from the diary of a member of the Seaman family, (Special thanks to my husband Patrick who had gathered information from the Seaman diaries on this topic).

Elizabeth Ford Seaman described how the flu epidemic was all around them, causing every church, school and public building to close. She related that there were very few families who did not have one or more deaths and that soldiers in camps were dying by the hundreds.

The family received a letter from a friend or acquaintance talking of the flu spreading through that family and quotes (quoted as written without grammatical corrections): “...never seemed such sadness all around us are death it is awful.”

Edmund Seaman was in the funeral business and became ill himself. His wife Edna had to carry on the sad business of handling funerals, not knowing if her husband might join others who had died. (He was fortunate and survived).

A trip had to be made to Patterson, New Jersey, for more caskets.

On October 23, 1918, from the Seaman homestead porch (now Palaia Winery), they watched several funerals pass along old Route 32 (which ran closer to the Seaman house then), observing that they had never seen so many in one day.

Five days later, a family member reported that there were nine funerals in eight days.

From September to November of 1918, at least five members of the Seaman family were in bed with the flu. Elizabeth was one of these and noted the few November diary entries due to being ill, including spending Thanksgiving in bed.

This would have been during the second wave of the pandemic. The Seamans were more fortunate than many of their neighbors - all eventually recovered.

On the last day of 1918, Elizabeth Ford Seaman likely summed up what many in the world were feeling: "This has been a very dark and gloomy month. I will be glad when it comes spring if I live to see it ....”